My friend Arun Bharadwaj planned an adventure trip to Kunukuntla, located in the Owk (spelled as “Avuku” in Telugu) mandal of Nandyala district, which was previously part of Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh. Nandyala, situated near the branch hill terrain of Eastern Ghats, is home to many devotional sites, including the famous Yaganti and Banaganapalle. It is also known for the great sage Veerabrahmendra, who wrote Kalajnanam, a prophetic text about future events, over 300 years ago and which even includes predictions about the coronavirus pandemic.

During our discussions, Arun mentioned prehistoric rock paintings in the stream gorges of this region, which sparked my curiosity. The area is known for its prehistoric site at Jwalapuram, not far from Kunukuntla, adding to the intrigue of what ancient inhabitants left behind.

Checking the terrain on Google Maps, the landscape looked arid and rugged, with sparse vegetation, quartzite rocks, and stunning gorges. Close to Owk, there’s an earthen dam built across the Paleru River, part of an ambitious irrigation project by the Andhra Pradesh government. This project lifts water from the Srisailam reservoir to feed three drought-prone districts in the Rayalaseema region, offering a lifeline to this arid land.

Our adventure began early Saturday morning on 24th August 2024, with Arun, myself, and our friend Rajeev, who generously drove the 700 km round-trip. After crossing the Karnataka border, we struggled to find a good vegetarian restaurant, a common challenge in the region. We eventually settled for breakfast in Tadipatri, which was passable, and packed food for the day ahead.

As we traveled further, we passed by limestone hills and the famous Belum Caves, dotted with cement factories due to the abundance of limestone in the area. We also noticed numerous black stone (Kadapa stone) workshops. This durable black limestone is known for its strength and resilience, often used in flooring and construction.

When we reached Owk, the sight of the large earthen dam impressed us. Originally built during the Vijayanagara period, it had been expanded to hold Krishna water, showing the area’s historical importance and the government’s dedication to farming.

Arun had arranged for a local guide, Mr. Anil Avula, a native of Avuku and a young entrepreneur from Hyderabad, to take us to the prehistoric rock art site. Accompanied by his friends, we set out for Kunukuntla, driving through a table-top hill that resembled the landscapes of Arizona, US. The vast plains and unique terrain were unlike anything I’d seen in Andhra Pradesh.

We crossed Kunukuntla village and arrived at Isranaik Thanda, a tribal village predominantly inhabited by the Lambani community. From there, we began a 6-7 km trek across a bare quartzite landscape with scattered small rocky boulders and shrubs. Along the way, we spotted blackbucks and wild deer, which quickly vanished upon seeing us, the “aliens” from the city.

Luckily, it was a cloudy day, making our trek easier. We descended into a large gorge (locally called “Pedda vaagu,” meaning big stream) with a fresh stream of water flowing below. The thick vegetation surrounding the stream added to the beauty of the place.

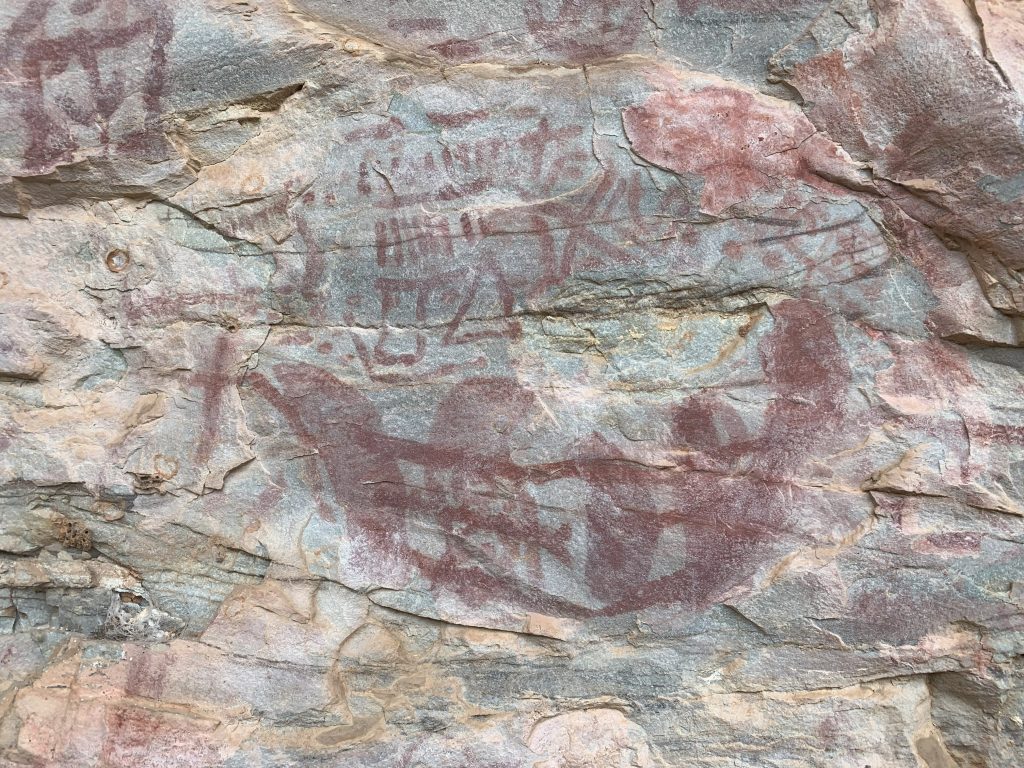

This gorge was home to Mesolithic (middle stone age) settlements, where prehistoric humans sought shelter under the rock formations. As we explored, the local team showed us breathtaking rock paintings. Among them was a depiction of a kangaroo-like animal and a fishing boat. This raised questions about how such images came to be in the Indian subcontinent, far from where kangaroos are native.

We also saw paintings of antelopes, snakes, and scenes of prehistoric humans hunting and gathering, all done in red ochre. Some of the paintings were in white, possibly created with limestone. These ancient artworks provide a glimpse into the lives of our distant ancestors, reminding us of human evolution and migration.

- Image 1: A Depiction of Boat with fishing in Prehistoric Rock Art

- Image 2: Depiction of a Kangaroo in Prehistoric Rock Art ?

- Image 3: Depiction of Prehistoric Cooking a Barbecue of Hunted animal in Prehistoric Rock Art painting

After trekking along the stream for 3-4 kilometers, we reached a serene pond with clear, bluish water. Anil Avula and his friends cooled off in the pond while we enjoyed snacks they had brought along, which gave us the energy for the next leg of our journey.

On our return to Isranaik Thanda, we encountered a local shepherd who, upon hearing about the rock art, humorously remarked that he too was a painter—though he painted houses! His lack of knowledge about the prehistoric significance of the area, which dates back to 10,000 BCE, was a poignant reminder of the need for preservation and awareness.

- Image 4: Along the Gorge: Scenic Views and Natural Wonders

- Image 5: A Rock Shelter in the Gorge Used by Prehistoric Human Settlements, Adorned with Rock Art Paintings

- Image 6: Water Flowing Through Gorge 2, as Shown on the Map

- Image 7: Exploring Prehistoric Rock Paintings in Gorge 2 with the Team

- Image 8: Large Quartzite Rock Boulders Used as Shelters by Prehistoric Human Settlements

We then headed to another gorge opposite the one we had visited earlier. The sun was setting, and in the fading light, we couldn’t explore as thoroughly as before. Some of the rock shelters here had been occupied by a sage, and sadly, much of the ancient art had been covered in limewash or damaged by modern graffiti.

As night fell, we returned to our parked car and thanked Anil and his friends for guiding us through this extraordinary adventure. Starving and in search of a pure vegetarian restaurant, we finally found one in Banaganapalle, where we stayed the night, preparing for the next day expedition.

Continues…

Leave a Reply